Writing Books for Curious People.

Brooks is a writer of books and stories; a student and teacher of effective communications; and a hall-of-fame researcher in the field of forestry.

Brooks loves reading and writing books.

Like other children, I pretended to be able to read the books that my parents read to me dozens of times. Over the years, when interested in a topic or waiting at a doctor’s office or sitting on the bus, I would read. To this day, I find wisdom, escape, and inspiration in books. Now, when curious about a theme or provoked by an idea, I study and write books. Please explore this site to learn more!

Services

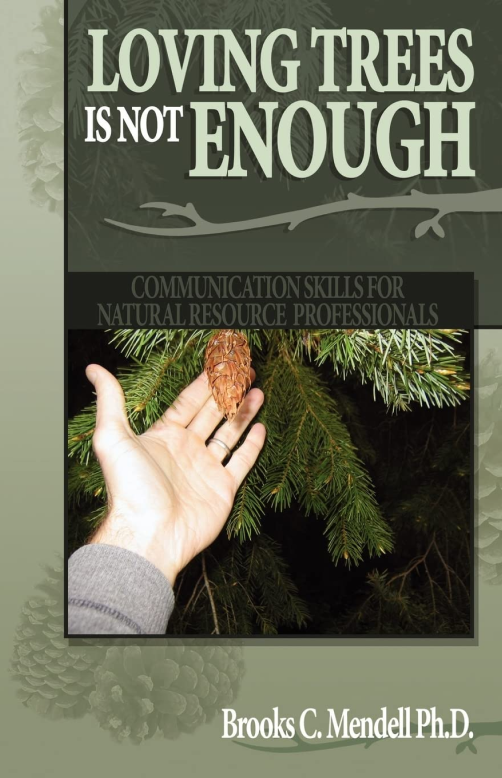

Books

Books by Brooks cover forestry and finance, leadership and communication skills, and a season with the MIT baseball team.

Learn More →

Speaking

An award-winning speaker and entertaining and engaging lecturer, Brooks delivers keynotes, presentations and workshops based on his books and on his experience in forestry.

Learn More →

Blog

Brooks blogs monthly on topics including books, writing, thinking, analysis, leadership, forestry, and sports.

Learn More →

Featured Books

Newest Blog

Testimonials

Great read for smart people who love sports

Great Book – A Must Read

Informative and Humorous!